On 19-21 September 2023, the two Dutch partners of our consortium (AHK & ICK) hosted the Premiere Open Days in Amsterdam. Showcases of the project’s four pilots, one round table discussion and a workshop took place at AHK IDLab and Culture Club. ICK curated the public discourse event FRA: AI, Creativity and The Body in Revolt at Space for Dance Art, questioning creative potentials and ethical aspects of the relations between technology, the performing arts and intuitive body knowledge. Speakers Kim Baraka (AI scientist and dancer), Julia Rijssenbeek (philosopher of biotechnology), along with Emio Greco (artistic director of ICK with Pieter C. Scholten), shared their perspective on if and how scientific research around (embodied) AI and artistic practices intersect and reveal that living bodies resist reduction to mechanical control or calculation.

Baraka highlighted some aspects of his research into human-robot relations via interaction, learning and teaching, including different fields such as human psychology, machine learning, cognitive/behaviour modeling and mechanics. He argued that knowledge embodied in artistic practices is relevant to inform the behaviour of robots (see also for example the NWA project “Dramaturgy for Devices”). Dancers carry an embodied knowledge of for example intent prediction, complex coordination and nonverbal communication, sparking curiosity about how dancers could pass on intuition and creativity to embodied AIs such as robots.

Rijssenbeek explained that lifeforms revolt against machine models forced upon them because they are characterized by instable, constantly evolving mutating and interacting processes. Lifeforms are also not reducible to parts-based mechanics, they are forms of becoming which cannot be isolated from their environment. Living bodies are always interacting with the environment and with each other. They are not passive material that one can steer top down by a central intelligence like a gene or the brain. Living matter embodies a cognitive dimension. Rijssenbeek thus invited the audience to critically reflect on the limits of approaching life through technological control and calculation.

Erik Lint (AHK ID-Lab) engaged in a dialogue with Emio Greco about the reasons for Greco and Scholten’s longstanding and ongoing interest in working with new technologies.

Emio Greco: “Besides its physiological and biological function, I consider the body as pure technology. The way it interconnects information, the way it is is transmitted and how it is received – that’s where I see technology. From this departure point, Pieter and I can be in dialogue with an external technology. The dimension of communication through bodily technology I define as ‘energy’: it is not a fuel to burn, but a presence in and around yourself. It is an augmented body that informs and anticipates the body in motion. For example while coming towards another your energy anticipates your body, thus the person in front of you already understands with which kind of information both are going to meet. There the real listening takes place, and it happens in the invisible; it’s not something you see of the other, but it is the recognition of the information produced, or let’s say ‘proposed’ by the energy.”

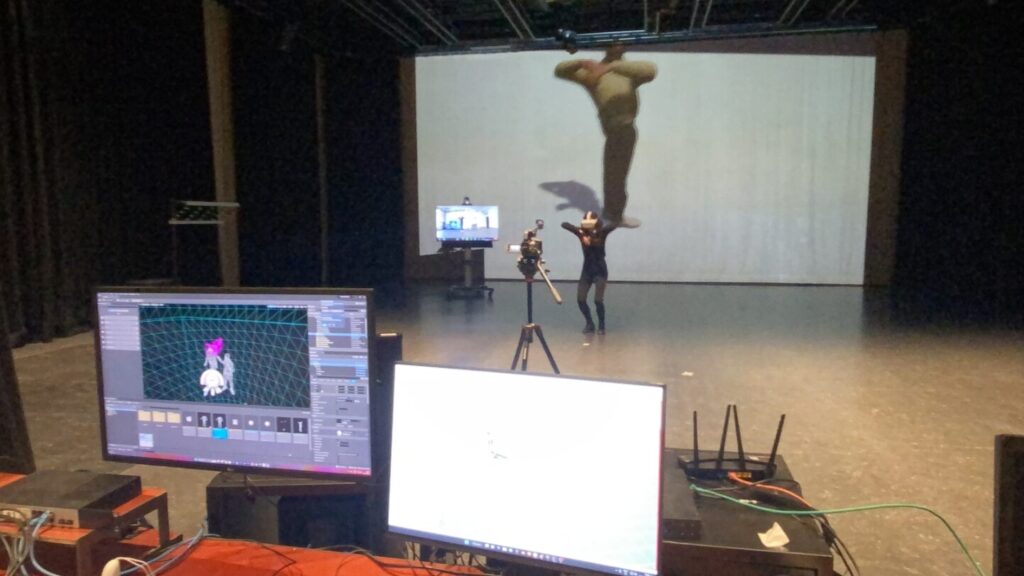

Problems and potentials of relating the intuitive body of a dancer with technology thus lie in how such organic expressions of the dancers’ inner life might be augmented in an XR/AI-informed world, beyond a simple visual representation. And besides corporeal presence, movement sequences are embodied by the distinctive physicality of a dancer with a unique energy: a precise scan of a dancer’s unique features transposed into a universal avatar shows thus far only a mere image of corporeality.

This node of virtual representations of bodies and physical presence also calls for a reconsideration of ‘reality’ and ‘doubt’. In a ‘post-truth’ era of ‘fakes’, what does it mean to establish (physical) corporeality as ground truth? Can datasets reflect the experience of physical presence? Emio Greco considers the artistic process of dance to be a mixture of hypotheses and decisions: “We are talking about intuition and intuitive bodies and that is always a presumption. There is nothing scientific about that, it is not a certainty, therefore you remain in a guessing mode, in an ‘if’ state. But at a certain moment you need to give your trust, to name it and to take a position; you have to make a statement. Intuition is related to detecting the momentum while dancing and to give it a way to develop and to expose itself.” Reflecting on the efficiency of the body, he further articuletd: “the human body is self-sustainable, it can immediately resolve a problem or a mistake or a clash that occurs in the movement. In the reflection between mind and body you dialogue with the direction towards which you want to move your body. You can take advantage of that mistake and turn it into a positive sense. The outcome of this solution is an awareness that is distributed between body and mind.”

To Erik’s question about where the mind lives in Emio’s body – where it is located – Emio responded: “There is a way to experience the detachment of oneself from a situation, from an action, the self from the body. To take a little bit of distance from the self or becoming completely part of the movement. Delaying the moment of mentally acknowledging an ‘instinctive’ movement is also a training process. That’s why our first performance was called Between Brain and Movement: to understand who is what, and what relates with what. Sometimes, you may say, the mind is spread everywhere like the brain of an octopus, distributed, multiplied into all points of the body; sometimes you might experience the mind as an aura of knowledge above the head while something else is at the same time more grounded in the body. The territory of the mind can shift and you can separate different attributes of it. It is a bit difficult to understand; it belongs to the mystery of practicing dance, and somehow, without fully understanding it, the movement shows it. This scenario needs a witness, and the spectator is also part of the performance. First the performers need to be clear for themselves before a dialogue with the audience can happen.”

Spectators receive a mirroring impulse of what they see on stage. Can XR/AI augment the audiences’ physical, emotional, intellectual response and even affect in real time the behaviour of (virtual) humans or (synthetic) dancers? Augmenting the agency of spectatorship through (in)direct feedback, and allowing a broader diffusion of performances, is what in this sense might be reframed as ‘accessibility’. That and many other aspects of the co-evolution of biological and artifical technologies ICK aims to discover together with the consortium during the creative process of PREMIERE, perceived as a scientific and artistic experiment and as a transformative experience towards a yet unknown future that we are shaping together.

Suzan Tunca

Francesco Cutillo

ICK Dans Amsterdam/Space for Dance Art